Juni Sun Neyenhuys

As a creative researcher and designer, Juni Sun Neyenhuys dedicates herself to the development of innovative biomaterials and conceptual design. With a background in Product Design from the Berlin University of the Arts and in Textile and Material Design from Weissensee School of Art and Design, she aims to repurpose natural resources within ecological cycles. Her fascination with algae and its potential led her to work on algae-based materials since 2018, supported by a study scholarship and a startup grant. In the spring of 2020, she travelled to Japan for research purposes—an experience that inspired her to co-found the startup mujō (Japanese for "impermanence"). The company focuses on developing biodegradable, algae-based packaging and won the 2021 "make tomorrow new" award, which enabled further development of the technology and product. Her work combines creative solutions to complex challenges and aligns future visions with ecological sensitivity, technological feasibility, and economic viability.

Interview with Juni Sun Neyenhuys

Juni, you went on a research trip to Japan in the spring of 2020: Why, and what did you take away from it?

II’ve always been fascinated by Japanese craftsmanship and material culture and wanted to explore it more deeply. Specifically, I came across the word “Aichaku”, which describes an emotional attachment to an object. John Maeda writes in his book “10 Laws of Simplicity”:

“The Japanese language uses the term ‘Aichaku’ to describe emotional attachment to an object: It is a kind of symbiotic love for an object rooted in animism, which deserves affection not only for what it does but for what it is. If we acknowledge that there is Aichaku in our designed environment, we can make a better effort to design objects that evoke three things in people: feelings, care, and the desire to own them for a lifetime.”

In a consumer society where product life cycles are becoming increasingly shorter, it raises the question of how to extend these cycles. Specifically, I wanted to explore how, and if, Aichaku could be intentionally created within the design process. This became the starting point for my journey to Japan, where I visited various artisans and interviewed them on this topic.

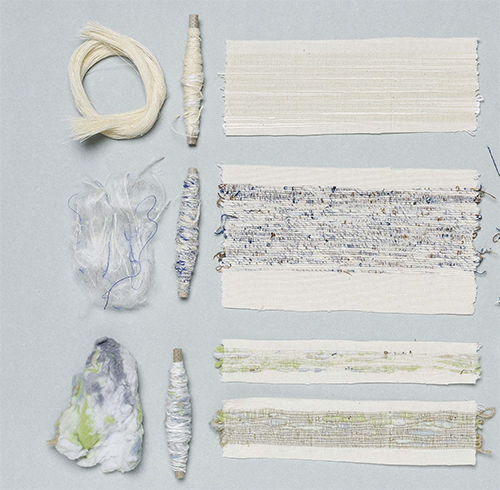

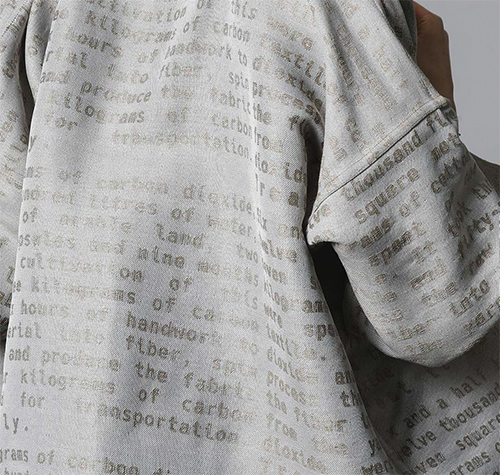

Interestingly, all the artisans agreed that people develop Aichaku for an object when they associate stories with it. This insight led to the creation of the Re.Code project: textiles that can be personalised by transforming personal stories into patterns, which are then woven into the fabric.

Tell us a bit about your start-up, mujō: Where are you today with the start-up? How much courage did it take to start? And what’s the biggest challenge?

We founded mujō at the beginning of 2021, while I was still in my undergraduate studies. From my perspective, it didn’t actually take that much courage. We had our team, and we received a lot of encouragement and support (including from our mentors at the Weißensee Academy of Art with Prof. Dr. Zane Berzina and Prof. Dr. Auhl, as well as Konstanze Schäfer and Andreas Salomon from TU Berlin). What really carried us far, I believe, was our naivety – having no idea what we were truly getting ourselves into (aka revolutionising the packaging industry).

Winning the Make Tomorrow New Award allowed us to fully focus on product development and building the company. Over the two years following my bachelor’s, I learned an incredible amount – and, of course, made plenty of mistakes along the way.

For me personally, things changed quite a bit at the end of 2023. I stepped down from my role as a shareholder and co-CEO and am now part of the company as a designer. I’m very happy about this development because this role aligns much better with my strengths and allows me to pursue my master’s degree in Helsinki.

You received a scholarship from the German Academic Scholarship Foundation (Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes) and a start-up scholarship from DesignFarm Berlin. How important were these scholarships for your work?

Without these scholarships, I wouldn’t be where I am today. So, yes, they were incredibly important. The Studienstiftung not only provided monthly financial support but also enabled my research trip to Japan, for example. The start-up scholarship from DesignFarm Berlin was equally crucial, as it allowed my team and me to focus entirely on our project for six months while benefiting from countless hours of mentoring from experts.

You describe yourself as a mediator between clients and science. How do you manage to balance both worlds?

When developing a new technology or material, immediate feedback from the market and customers is essential—otherwise, you risk creating something that doesn’t meet market needs. Material innovations require specific applications. I find this "sitting between the chairs" role incredibly exciting. I’m neither a hardcore scientist nor a 100% designer but positioned exactly in between.

This means I read academic papers and conduct experiments while also using rapid prototyping tools and developing products, concepts, and applications for new materials. Science provides the technical foundation for material innovations, while design makes the future of materials tangible.

And what does your collaboration with scientists look like?

Communication is key in such collaborations. You need at least some understanding of the specialised topics to avoid talking past each other. Designers are used to fast, experimental, and intuitive prototyping. From my experience, scientific work is a bit slower-paced. You need to adapt to this rhythm because every experiment has to be well-documented, and you can’t just wildly change multiple parameters at once.

On the other hand, the designer’s approach of quickly trying something out can be beneficial for science. Instead of reading five papers and meticulously planning an experiment, sometimes an initial “trash test” can yield valuable insights.

For a circular economy, sharing knowledge will be essential. There are already quite a few players working with algae. Is there any collaboration happening?

Yes, it’s great to see that more and more start-ups worldwide are developing materials from algae. We’ve exchanged ideas with many of them. Everyone agrees that collaboration on transformation processes is crucial – for instance, strengthening European algae farming or establishing political frameworks in the packaging sector, such as a comprehensive disposal infrastructure.

The packaging market is enormous, so there’s enough room for everyone. Personally, I’m a big fan of open-source hardware technologies and firmly believe that open source is essential for implementing a circular economy.

What do you hope for in your professional practice, from the economy, politics, and society?

I hope that design in the field of material innovation will be valued and integrated as an essential component. For example, I think research institutes should include design teams to develop applications. Designers can do so much more than just make products look appealing. In Germany, it’s possible to pursue a PhD in almost any scientific field – so why not as a designer?

Specifically, I’d like to see political frameworks change so that companies contributing to environmental pollution with microplastics or driving climate change are held accountable. A first step could be implementing a CO₂ pricing system. Currently, these externalised costs are borne by society, and without regulation, material innovations will remain niche products. If the externalised costs were included in the price of plastic, it would be as expensive as our algae-based material—making us competitive.