Cornelius Richter

Critical thinking and childlike ease – Interview with Cornelius Richter

Cornelius Richter examines how material decisions shape perception and value, and designs recycled materials as an aesthetic element. For the product designer and research assistant at Folkwang University of the Arts, design is a space for experimentation, curiosity, failure and progress. His projects STUHL and re.form illustrate this unique approach with flying colours – earning Cornelius Richter multiple awards, including from one&twenty and the iF Design Awards. Most recently, he impressed the jury of the German Design Awards 2026 and is one of five Newcomer finalists.

Cornelius, you describe design as “making appropriate decisions.” How do you define appropriateness in design today?

The beauty of the term ‘appropriateness’ is that it is not concrete. In design, it addresses both social and personal values. Design always emerges in a ping-pong game with social developments. So when I say that making appropriate decisions is about these very values, they primarily reflect the present – i.e. economic conditions, political unrest and ongoing crises. In addition, the term can be used as a tool for fundamental questions, right down to very specific detailed solutions. It is about thinking about the material, manufacture, use and finiteness of a product. All in all, appropriateness does not promote a particular style or a particular time, but rather an attitude.

In STUHL, you adopt a childlike approach to creation. What can professional designers learn from that perspective?

In a two-day workshop, I drawed chairs with primary school pupils and made small-scale models of them. I then tried to apply the ‘design principles’ I observed in this workshop on a 1:1 scale. I found it surprisingly difficult to put my knowledge and skills aside and just get started without any inhibitions. In order to get closer to the associative and spontaneous actions of the schoolchildren, I therefore imposed rules on myself. For example, with the Zufallsstuhl, whose materials were selected using a generator. Or with the One Hour Chair, which had to be built in a maximum of one hour. This project has permanently changed the way I design. There is a phenomenon whereby design processes often return to the initial idea. Designers can draw inspiration from the childlike approach to design and harness the potential of spontaneity and association.

How does working with waste materials change your understanding of value and aesthetics?

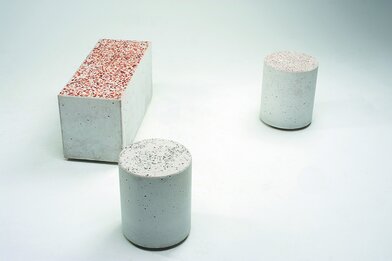

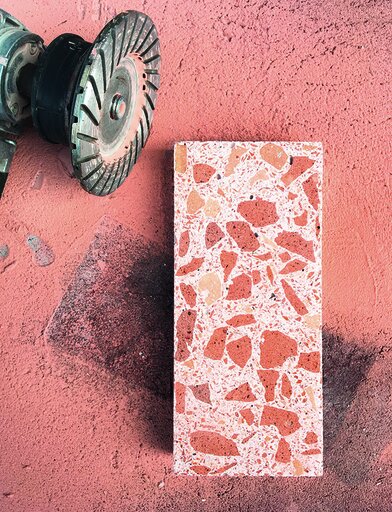

Before our understanding of value and aesthetics can change, our perception of value and materials must first change. This applies both to newer materials – I am thinking here of plastic, which is often looked down upon – and to waste materials. Waste is often colloquially equated with rubbish, which emphasises its supposed inferiority. To counteract this, I create concrete furniture for public spaces in re.form, using construction waste in its manufacture. Its sanded surface is more reminiscent of time-honoured terrazzo than waste. My aim is not to gloss over the construction waste, but to symbolically embrace a material and highlight individual materials as aesthetic means. A change of perspective on waste materials through a different context can contribute significantly to a positive shift in value.

Industrial design often follows efficiency and production logic. Where do you locate freedom within this framework?

As a product designer, I don't see myself as an author who has sole ‘sovereignty’ over the design. In my opinion, design should be flexible and allow for external influences from customers or colleagues. Limiting factors such as industry material and manufacturing specifications should also be seen as an additional incentive – not as a restriction on creative freedom. At the same time, I am a designer because I am fascinated by materials, form and manual work. It is therefore inevitable for me to let my own personality flow into my design work.

What does transformation mean to you as a designer?

Design is undergoing constant transformation. In my work, this means seeing a material not only as what it is at this moment, but also as what it can become. I address this material transformation in re.form: an urban building is demolished and its rubble is crushed into different grain sizes in a processing plant. This is then used as a coarse aggregate for the production of concrete. By grinding the surface, clinker, old concrete or broken asphalt are revealed, resulting in a varied surface. Processed into concrete furniture for public spaces, the city is perceived as a transforming place.